The Next Step

Reflecting on medical school, match, and preparing for residency

I have tremendous news…

On March 15th, 2024, I officially matched into the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation residency at the Medical College of Wisconsin! I will spend my first year of residency in upstate New York and then return to Milwaukee summer of 2025. I’m incredibly excited to match into my preferred specialty and to finally get working.

In the meantime, I’ve reflected on lessons learned in the trenches of medical school and wanted to share them here: lessons that are applicable to any goal or difficult period in our lives. But first… you are (hopefully) saying “congratulations!” as well as (probably) asking “what is match?”

The Match Process

Match is the process of how fourth-year medical students secure positions in medical residency programs to become “resident physicians.” It’s kind of like the draft - here’s how it works.

Students gather a bunch of information to submit into a database known as ERAS. Information includes transcripts, letters of recommendation, board exam scores, a performance letter called the MSPE, etc.

After gathering oodles of documents, students compile it into an application and submit it to ERAS in late September. ERAS then sends each application to whichever programs were applied to. For me, I applied to 50+ PM&R programs and 20+ Transitional Year programs for a total of 75+ applications.

Why two different types of programs? Some PM&R programs start in the second post-graduate year (PGY-2) meaning that I would need another program to cover my first year of training. This is where the transitional year program comes in - it is a specialized one year program for this purpose.

Next, residency programs review each application they receive and offer interviews to those applicants they wish to pursue. Applicants then attend interviews (via zoom, pretty much) until January/February the next year.

After interviews are completed, applicants and residency programs alike develop their “rank lists.” This is exactly what it sounds like. Applicants will rank every program at which they interviewed from most desirable to least. Programs will do the same for the candidates they interviewed.

Data from each medical specialty and every residency program participating in the match is then plugged into a specialized computer program and - voila! - it makes the best match.

Afterwards, on the Monday before Match Day, applicants are notified whether they fully matched, partially matched, or did not match. A full match means all of your residency training requirements are covered. A partial match means only some of your required years are covered (e.g. if I had matched into a Transitional Year program but failed to match PM&R). Those who did not match go through a secondary process called “SOAP,” which is essentially a mad dash between candidates, medical schools, and programs to fill any open residency position in any medical specialty.

Then… after all that… after four years of undergrad and four years of medical school… you find out where you’re spending the next three to seven years of your life on “Match Day.”

Lessons from the Medical College of Hard Knocks

Lesson 1: Chill Out

Like begets Like.

A funny thing about medical school is that students are put into positions to act as physicians… yet they aren’t. Simply put, there is a discrepancy between a student’s skill and the task to which they are asked to contribute. This discrepancy all too often leads to anxiety, fear, and, if left unchecked, despair. First, some context.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi is known as recognizing and naming the phenomenon known as “Flow,” e.g. being “in the zone.” This is the idea that there exists an optimal mental state where a person participating in some activity is fully immersed in it, resulting in enjoyment, increased focus, and superior performance. If you’ve ever watched Kobe play basketball, you know what I’m talking about. If you haven’t, here’s what it looks like.

One of the ways Mihaly expressed this idea is with a “flow channel,” which is depicted below. It’s the specific area between skill and challenge where it is easiest to enter flow. If one’s skill is too highly suited for the task at hand… they get bored. But if their skill is ill-suited? Anxiety and, at worst, panic.

This is the dilemma of the medical student. We have little skill compared to the complexity of tasks and we fall all too easily into anxiety. If optimal performance is the goal, and optimal performance is associated with flow, then how can a person reach flow when there’s such a discrepancy between skill and task? How can a person reach optimal performance when their environment is chaotic, stressful, and moving too fast? What’s the solution?

The solution is to chill out. No, seriously. Just chill out. That may sound insensitive and overly simplified, but I don’t mean it to be. Let me explain.

First, let’s separate “chill out” into two words instead of one phrase, so we can look at them as two dimensions of the same expression. We’re peeling back layers.

In this context, the first dimension - chill - conveys a powerful truth: that “I” am separate from my emotions. My emotions are not me. This separation reinforces a person’s choice on how they ought to act and what they ought to believe. Simply put, just because I feel a certain way does not mean that I am required to act that way or believe that feeling… e.g. “I don’t feel chill, but I will act chill.”

As a medical student, the hospital environment is overwhelming and the skill–task discrepancy emphasizes this overwhelming feeling. One may feel inadequate as our skill level is, at times, literally inadequate for the task at hand. We are novices. As a result of this we end up digging foxholes in the no man’s land labeled “Anxious!” The trick, then, is to understand that though we may feel inadequate, it does not naturally follow that we are inadequate. Do you see the difference? A feeling is certainly valid, but that does not make it true. Understanding this separation between “being” and “emotion” keeps us in control, not our feelings.

The second dimension - out - refers to the fact that our actions influence our environment. An example: an object in motion will stay in motion unless acted upon by an outside force. Here it is tweaked a bit: a chaotic environment will stay chaotic… unless acted upon by an outside force. That’s where we come in. By choosing to chill outwards, we take the first step in changing our environment by changing ourselves. That’s the game: either we master ourselves or our environment masters us.

That outward movement will breed more of the same. Objects in motion will stay in motion. Objects at rest will stay at rest. Plants beget plants. Animals beget animals. Chaos begets chaos. Confidence begets confidence and…

Like begets Like.

The solution to this anxiety-inducing dilemma is actually the first task the student must learn: self-mastery.

Lesson 2: Get off the bench

Character over competence.

Medical school is filled with successful type-A over-achievers. This is a good thing. Patients do not want lazy under-achieving future doctors. However, an unfortunate side effect is that this success, at least up until medical school, has been defined as perfection. Perfect grades, perfect resumés, perfect references, etc. But once we get into medical school and into the hospital, this sense of perfection is not our friend. In desiring perfection, we fear imperfection. In fearing imperfection, we stay on the bench, out of the game, and don’t take opportunities to learn new skills or participate more deeply in a patient’s care.

This fear is based on the belief that, to be the best physician one can be, one must be the most knowledgeable and competent. Medical school is where a doctor’s foundation is laid and the assumption is that this foundation is made strongest when based on intelligence. One may say something like, “the more things I know, the better I’ll be.” In a way, the student accidentally lumps intellect and capability together and places these as the ultimate markers of success. To medical students, who are novices, this is simply not true. The foundation of good medical practice and good doctoring is based on character, not competence. Now having expressed this, I must say that the ideal doctor is both highly virtuous and highly capable. However, character must be emphasized as a clinician’s foundation because competence often develops from sound character, but character rarely develops from talent and skill.

To be as clear as possible, I am NOT saying that competence is unimportant. Quite the contrary - competence becomes most effective when based on character. A physician of strong moral fiber will be a better teammate, leader, communicator, and will be humble, always looking to learn for the betterment of their patients. They will perpetually improve their craft. A physician of weak character, no matter how smart they may be, will be much more tempted to cut corners, communicate poorly, and be arrogant, thinking they know best at all times. They will be unwilling to admit their mistakes - and all doctors make mistakes. With the physician of weak character, patients suffer needlessly.

Competence can be taught, but character cannot - it must be developed. In the context of learning, the first step to developing character is to get off the bench and into the game. In doing so, you are choosing discomfort. You are choosing confusion and pain and awkwardness. You are choosing to acknowledge imperfection; to be imperfect now with the goal of being perfect later. This is a sacrifice and sacrifice is the mechanism of developing character.

An analogy: character is the soil to competence’s rose. The richer the soil, the more fruitful and beautiful the blossom. It is the student’s task to garden with patience and conscientiousness, focusing on virtue while allowing their clinical skills to mature naturally over time.

Continuing with our analogy, the student who fails to develop their character becomes a doctor who is like a plastic rose. From a distance, the plastic rose looks beautiful and you may be fooled into thinking it’s real. It may be so well-designed that it fools you even when you’re up close! However, as time goes on, everyone will come to see that this “rose” is anything but real. Its petals are far from pleasing. It stinks of industry and fabrication. It has no true thorns or sepals or peduncles… no xylem or phloem. It is, to your dismay, a feeble attempt at imitation. A cheap knockoff. When compared to an actual rose, one may even call it pathetic. And if the imitation is poor enough, one may even consider it mockery. Such is the physician of low moral character.

Don’t be that.

Lesson 3: All systems go

Be a rocket, not a bomb.

What’s the difference between a rocket and a bomb? Direction.

A rocket and a bomb are both expressions of energy. A bomb explodes in all directions, whereas a rocket explodes in just one. The idea being that a rocket channels and restrains its energy to go a certain direction, just like a person who wishes to achieve a certain goal needs to channel and restrain their energy towards one objective. A rocket must have good systems in place to keep its course. The same is true for people and organizations. Good systems are important in running businesses, military operations, sports teams, families, etc. Yet, in my experience, few people understand the importance of running systems on an individual level. I say this because I was once one of those people.

Entering medical school from the workforce was difficult and I had no idea how to study, let alone study for medical school. This was evidenced by my first exam where I was told I failed by one question… woof.

One thing was clear: I needed to change.

I retooled how I studied and became more focused. I scheduled my time better, re-emphasized exercise, and took advantage of school resources I hadn’t before. As a result of these changes, I passed the next test with flying colors. The punchline, as fate would have it, was an email that came soon after my second test. Turns out there was an error when scoring the initial exam: I had actually passed! Though, admittedly, barely. However, that scoring error turned out to be a blessing in disguise as it provided both the opportunity and motivation to completely overhaul my study systems.

Systems also help clinically. For example, a solid framework when interviewing and examining patients is imperative to developing differential diagnoses and treatment plans. Generally speaking, if I have a system to gather information, and it produces good results consistently, then I know I can rely on that system. I can trust myself.

An example of a system I use is called the OODA Loop, pictured below. Originally developed for dogfighting by USAF Colonel John Boyd, the OODA Loop has proven itself an effective decision-making tool in the military arena as well as others like business and law. OODA is an acronym that stands for Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. I found it to be extremely useful rotating through the hospital. Let’s see how it works.

Here’s the scenario: you’re a new medical student on an inpatient medicine team. Go.

Observe: What is the culture of the hospital? What is the culture of your team? What is the layout of the wards and where are your patients?

The team is structured in a hierarchy with your attending at the top, followed by your senior resident, then two junior residents, and you at the bottom. You are assigned four patients to follow.

Orient: What is the goal of your team? What is your role on the team? What are your personal goals? What are you trying to accomplish?

Your role on the team is to know your patients “front and back.” Your goal for this rotation is to build solid patient rapport. Your team’s goal is to successfully diagnose and treat all patients to the standard of hospital-wide quality control initiatives and measurements.

Decide: Make a decision to act in a way you believe will be useful towards you and your team’s goals.

You decide to spend extra time with your patients after morning rounds. You believe the extra time will foster good rapport and increase patient satisfaction, thereby improving their hospital experience.

Act: Do it and see what happens.

You spend 10-15 minutes or so, time-permitting, with each of your patients after lunch.

After you act, you are back to the “observe” portion of the loop, looking at the consequences of your actions. What’s the feedback you’re getting? Are your actions in line with your goals? Getting real-time feedback, the OODA Loop is a great tool to consistently hone your skillset and keep you focused on your goals.

Side note: Additionally, I found the OODA Loop pointed me to where I could add value to the team, albeit indirectly. As a new student in the hospital my medical knowledge was low (as discussed in the previous lesson). However, relative to my team members, I had lots of extra time! Using that time effectively, e.g. spending more time with patients, led to a sense of fulfillment and accomplishment, making the discomfort and confusion of learning much more tolerable.

Reaching goals is much harder than setting them. To reach them, you must develop good systems that provide useful feedback to keep you focused and on track.

Lesson 4: Bob and weave and take a punch and move.

Get gritty and resilient.

Note: This section contains discussions of death, abuse, suicide, and homicide. Reader discretion is advised.

Stuff happens. Stuff will always happen, both inside the bubble of medical school and outside. But no matter what happens, you must keep moving. You have to bob and weave. You’ve got to learn to take a punch. You can’t get knocked off your path.

Unfortunately, I had to learn this the hard way. But that’s a story for another time.

A common thread running through medicine is the reality of evil. And yes, I use the word “evil” deliberately. Disease and death are natural evils of this world. Their goings-on make up a physician’s day-to-day.

Over the course of my schooling, I gained a lot of experience in dealing with these evils. In almost all of my rotations I saw the slow, yet aggressive, ravages of cancer. In my surgery rotation I pulled harmful tumors and diseased organs out of people’s bellies. In my emergency and psychiatry rotations, I spoke with people in debilitating psychosis. I have encountered people experiencing the sudden doom of acute injury as well as the slow burdening of chronic disease.

I’ve also experienced the unique human aspect of evil with which a physician must grapple. In my family medicine rotation I witnessed child abuse. In my pediatric PM&R rotation, I saw multiple cases of developmental delay that were consequences of non-accidental trauma. In my emergency rotation, I treated patients who were victims of assault, gang violence, and trafficking. And, most distressing of all, I performed multiple autopsies and witnessed firsthand the gruesome horrors of premature death, decay, suicide, and homicide while rotating through the Medical Examiner’s office.

This is just an overview of some of the things I experienced during my time here in Detroit. Yet, life outside medical school did not stop. Over the course of five years (four years of medical school and one year of research), I faced three neighborhood shootings, two depressing breakups, and one traumatic car crash. Though, I’m positive my experience is not unique.

The question becomes, how to respond?

The answer is grit and resilience.

Medicine is difficult. It demands you meet its high standard and resists any attempt at lowering that standard. Medicine demands that those who wish to practice it must be built into physicians. This process is grounded in grit and resilience.

Grit can be thought of as unyielding resolve or courage. Resilience can be defined as the ability to withstand difficulty. When applied, a person can move through any obstacle and recover from any setback. This is what makes it so useful in learning and practicing medicine - these traits keep you moving. If you can’t run, walk. Can’t walk? Then crawl. Can’t crawl? Talk to whoever you need to and breathe as slowly as you can. If you can’t move your arms and legs, then move your lungs and tongue. Whatever you do, you must keep moving.

Due to the nature of medicine’s high standard and inherent adversity, it’s almost as if one unconsciously becomes gritty and resilient. I mean to say that one doesn’t stop and think in the middle of adversity that they are “developing grit and resilience.” That’s ridiculous. It’s only after enduring adversity that one realizes what they have lived through and accomplished. You look back and see how far you’ve come. That reflection leads to the realization that the mere fact you sit here now means you have successfully navigated adversity with all its trials and tribulations. This reflection is necessary for becoming gritty and resilient because it makes you conscious of your developed abilities. It makes you conscious of the fact that people with grit and resilience successfully navigate adversity. That’s you.

Grit and resilience are necessary traits for life, success, doctoring, and residency. And they are always necessary for taking the next step.

Thank you for reading this article from Building Docs. If you enjoyed this article and got something useful out of it, please like it by clicking the heart at the top, share it with your friends and family, and consider subscribing for free if you have yet to do so.

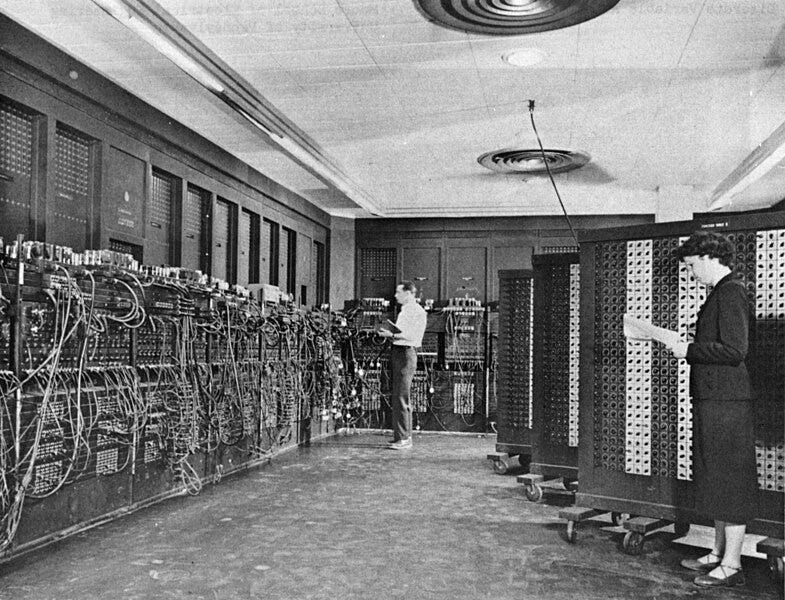

(1) Picture is free use from wikipedia commons - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Glen_Beck_and_Betty_Snyder_program_the_ENIAC_in_building_328_at_the_Ballistic_Research_Laboratory.jpg

Tyler, your excellent reflections are evidence of the model medical student you have been throughout your medical education here at Wayne. The life lessons you have distilled out of your own experience will carry you through the rigors of residency training and well beyond for a rewarding career. Your patients and colleagues will thrive under your care and dedication to your profession. As your Student Affairs Dean these last 5 years, I could not be more proud of you and look forward to seeing you cross the stage at Commencement! Dr. C

Tyler, The immense pride we feel for your journey, thus far, cannot ever be voiced with enough congratulatory and enthusiastic words! You continue to impress us with each level you've achieved and the man you are growing into is a continuing source of awe and our true happiness for the path you have chosen for your life. All the wisdom you are acquiring and the lessons you are learning will truly benefit your future patients and everyone in your orbit. The life lessons you've pointed out in this article can be applied to anyone, anytime, and in any situation and be completely adaptable to their individual circumstances. We love you and wish you the very best as you reach your next milestone.

Tom and Bernice