If you can see it, you can diagnose it. That rash? Shingles. Your ankle hurts? It’s sprained. But not everything sick shows up on the surface — in fact, most things don’t.

Since Clark Kent never went to medical school, we rely on other senses — namely our ears, tuned to both patient and body. Enter: the stethoscope.

Start with Anatomy

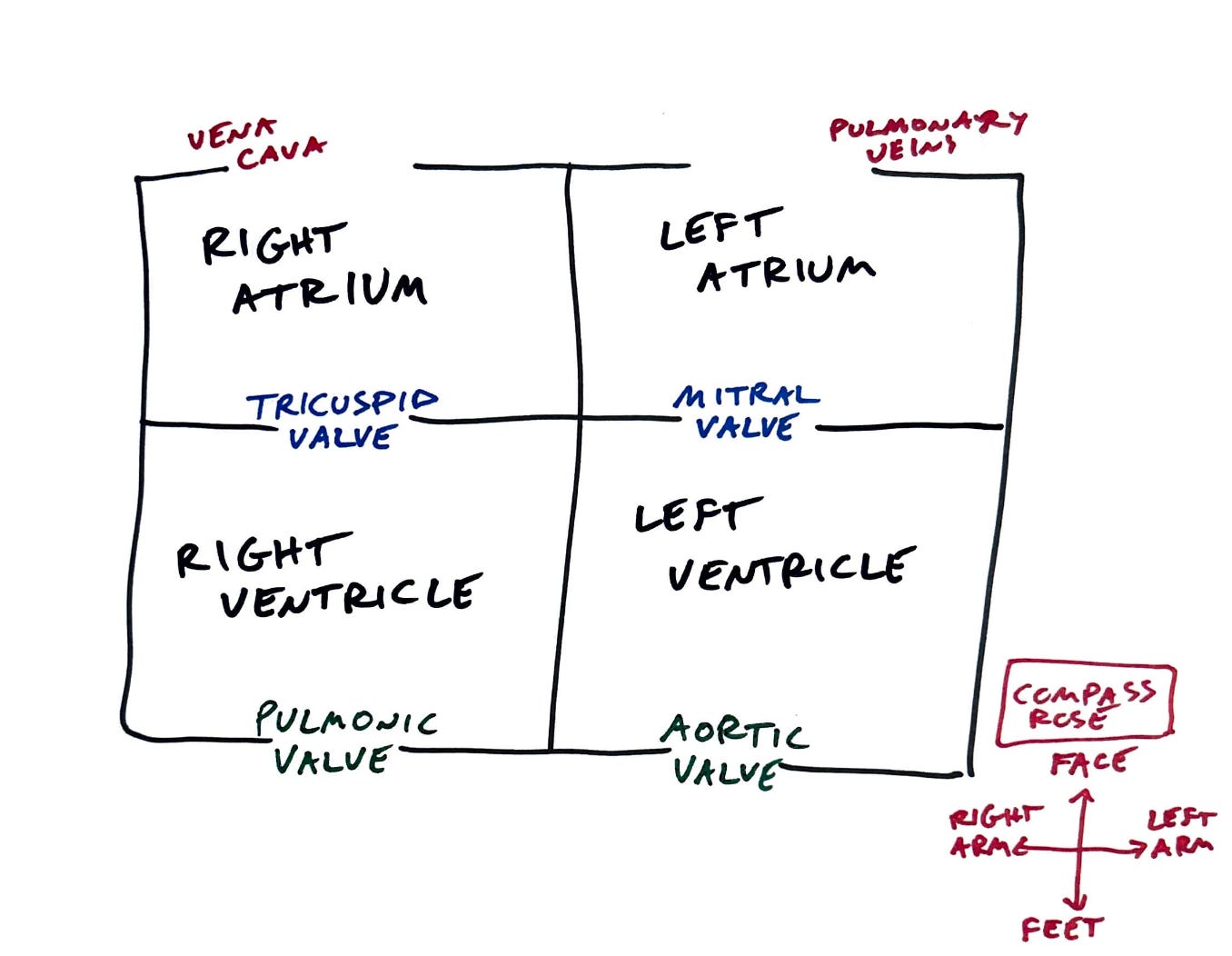

Let’s keep it simple. Think of the heart as a box with four chambers. There are two sides (right and left). The top chambers are the atria and the bottom chambers are the ventricles. Blood flows in one direction through each chamber — from right to left and from atria to ventricle.

For example, if we were to trace the appropriate flow of blood through a healthy heart, we would begin in the right atrium and travel to the right ventricle. From there, we go to the lungs via the pulmonary arteries. Now armed with oxygen, we return to the left atrium via the pulmonary veins and finally the left ventricle where we are pumped through the entire body via the aorta. Blood then returns to the right atrium via the body’s largest vein: the vena cava.

The heart is a muscular pump and its contractions drive blood forward. However, between each chamber sits a valve that controls flow, like doors in a house. There are four: the tricuspid, pulmonic, mitral, and aortic. They are pictured below.

Since valves open and shut like doors, they should sound like doors. This belief led René Laennec to develop the prototypical stethoscope while caring for patients in a Parisian hospital in the early 19th century.

If a heart valve closes, and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?

Turns out he was right! When a valve slams shut, it makes a sound — one you can hear, if you know where (and when) to listen. Go figure.

Atria and ventricles pump blood in an intricate dance. We won’t go too deep, but here is the big picture…

This dance involves the mitral and tricuspid valves closing together, called S1. Aortic and pulmonic close together, called S2. Together they make the classic lub-dub.

To dig a bit deeper… when the tricuspid valve closes (S1), the pulmonic valve opens and the right ventricle contracts to send blood to the lungs. The same is true on the left: mitral valve closes, aortic valve opens, and the left ventricle pumps blood throughout the body.

In medical speak: systole is when the ventricles contract (beginning of S1). Diastole is when the ventricles fill with blood (beginning of S2).

But where to listen?

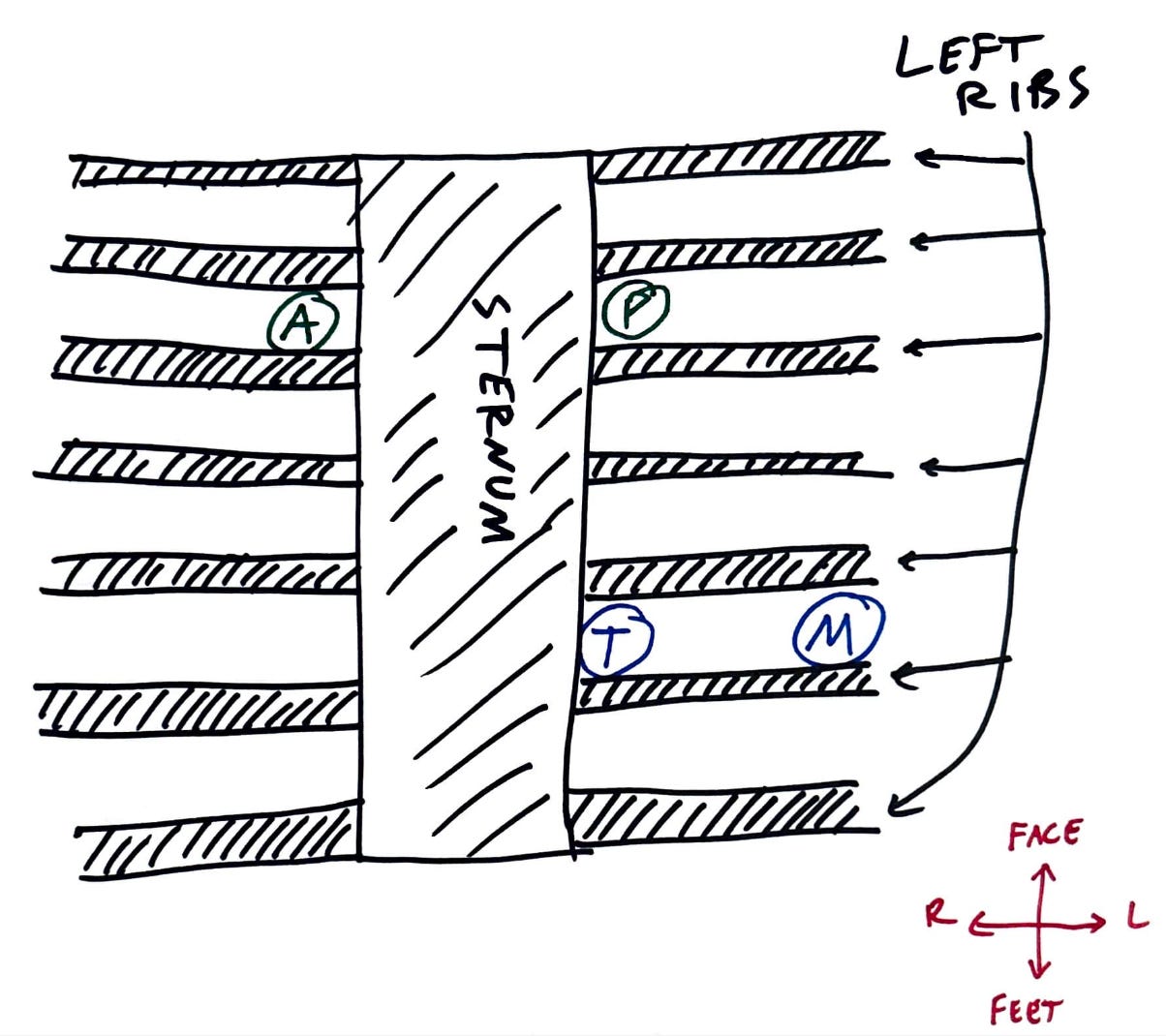

You may have noticed your doctor listens to multiple points on your chest. These points associate with specific valves. Here’s where you place your stethoscope:

Aortic: Right Upper Sternal Border

Pulmonic: Left Upper Sternal Border

Tricuspid: Left Lower Sternal Border

Mitral: Midclavicular line, in between the 5th and 6th ribs

Hearing Pathology

Valves, like doors, can malfunction. Doors may be too loose or too sticky. They may not fully open or may not close tightly. The same is true of heart valves: they can narrow (called stenosis) or they can become floppy, leading to a back flow of blood called regurgitation. These will cause sound changes during auscultation.

For instance, if you hear a whooshing in the right upper sternal border that occurs during systole (that is, while the aortic valve is open), then that would correspond with aortic stenosis — a systolic heart murmur.

Say you’re listening in the same spot, but this time hear an abnormal sound during diastole (while the aortic valve is closed). This would indicate blood leaking back through the closed valve: aortic regurgitation.

These rules apply to the other auscultation points as well. Diastolic murmur best appreciated in the left lower sternal border? Tricuspid regurgitation. Systolic murmur best appreciated left 5th rib midclavicular line? Mitral stenosis.

In Conclusion

To recap our basic crash course…

The heart has four chambers and four valves

These valves open and slam shut like doors

Each valve corresponds with a particular point on the chest.

S1 = lub = systole = ventricles contract. This is essentially your pulse

S2. = dub = diastole = ventricles fill with blood

Valves can be narrow (stenosis) or leaky (regurgitation).

Always remember — to hear is to see… if you know what you’re listening for.

*******

Thank you for reading Building Docs. If you enjoyed this article please consider liking, sharing, and/or subscribing. All three will help this publication grow — one of my main goals. Thanks for your support!

Tyler a very thorough exam by listening to your stethoscope. Liked the reference to Dr. Horton Hears a Who!!! I love how you analyze everything about a patient and then deliver a conclusion as to how to go forward from there. You will be an excellent doctor and your patients will be lucky to have you!!!